Image: Washington Crossing the Delaware, Emanuel Leutze, 1851, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Revolution in Black American Life: Sources and Evidence

On this page, we take a look at some of the people and sources we are using for our collaborative research project, The Revolution in Black American Life (with Clare Corbould). In this book, we will tell the stories of dozens of African Americans who have wrestled with the contradictions of the Founding, from 1776 to today.

Starting with enslaved Africans in the Revolutionary period itself, each chapter will focus on four different people to illuminate the varied experiences of African Americans, and the multiple and evolving meanings of the American Revolution across time. Readers will be introduced to some new figures such as Jeffrey Brace of Connecticut, who literally fought for his freedom in the Revolutionary War, along with some more familiar African Americans such as James Forten and Gabriel Prosser, each of whom challenged the legacy of the Revolution in diverse and unique ways.

In narrative form, each chapter will look at a new generation of African Americans and the ways they contested or co-opted the meaning of the Revolution through education, rebellion, wartime participation, memorialization, music, pageantry, television, and politics. Along the way, readers will also be introduced to new kinds of sources for the study of African Americans, including early black memoirs, pension applications, newspapers, school syllabi, oral stories, church sermons, political speeches, screenplays, art, music, and film.

This is an ongoing project, and we will add content periodically. To learn more about this project, click here.

Prince Saunders and the Haitian Revolution

Prince Saunders dreamed about securing the full promise of the Revolution. Only Saunders wasn’t interested in the American Revolution. Like Gabriel Prosser and many other black Americans in the early republic, he looked to Haiti. Traveling back and forth between Haiti, England, and the United States, Saunders published a collection of documents about Haiti and its revolutionary past, and lectured to different audiences in the United States. The documents reveal Saunders' keen desire to establish a universal and Christian public education system that would benefit African Americans, and his belief that the best place to achieve this would be in Haiti. He was also keen to encourage the emigration of African Americans to Haiti, which he called the "paradise of the New World." While his emigration scheme met with mixed results in the 1820s, Saunders' helped encourage a new generation of free blacks to look to Haiti for revolutionary inspiration. He lived there until his death in 1839.

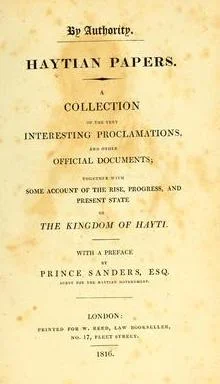

Prince Saunders, Haytian Papers (London, 1816)

After visiting the Kingdom of Haiti and meeting King Henri Christophe in 1816, Prince Saunders published the Haytian Papers in London that same year, and then subsequently in Boston in 1818. It includes a collection of Haitian proclamations, decrees and other documents with commentary from Saunders, as well as a short history of Haiti.

In his preface, Saunders extolled the virtues of Christophe and the Kingdom of Haiti, and the “enlightened system of policy…and liberal principles of the Government,” as well as the “ameliorated and much improved condition of all classes of society in that new and truly interesting Empire.”

Prince Saunders, An Address Delivered at Bethel Church...Before the Pennsylvania Augustine Society for the Education of People of Colour (Philadelphia, 1818).

In his address to the newly founded Pennsylvania Augustine Society for the Education of People of Colour (whose First Vice President was James Forten) in Philadelphia in 1818, Saunders argued for the importance of a universal Christian education for African Americans, asserting it was essential to improving their lives and their status among whites.

In this he laid the groundwork for a continued argument that African Americans should think about Haiti. He cleverly noted that it was only in the northeastern parts of the United Stated, “some portions” of Europe, and in Haiti, that “enlightened men” were actively working toward the goal of universal education.

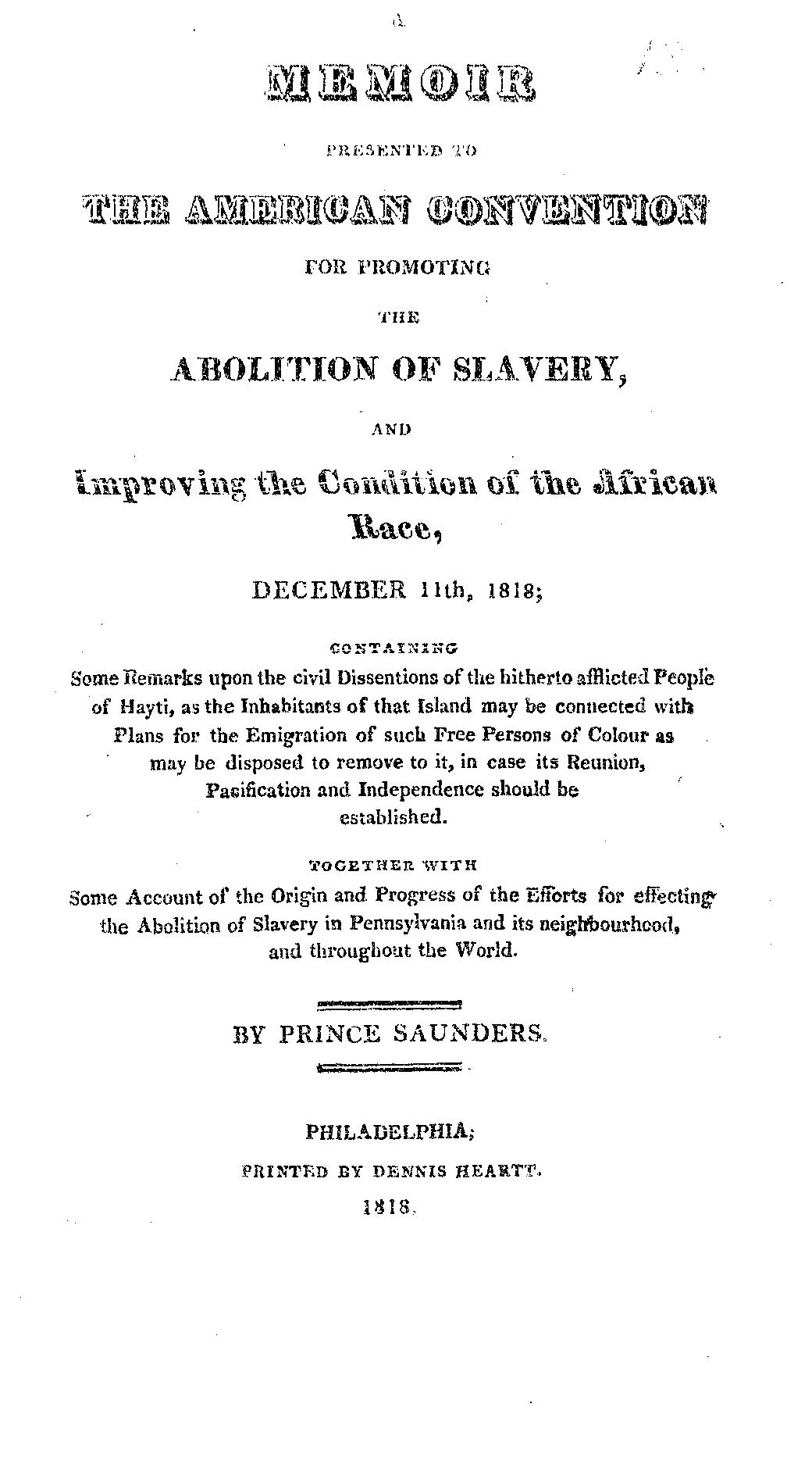

Prince Saunders, A Memoir Presented to the American Convention for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery.... (Philadelphia, 1818).

When Prince Saunders spoke to a room full of distinguished abolitionists in Philadelphia, he asked that they support an effort to try and unify Haiti and bring peace to the island. Not only would this allow he and Henri Christophe to implement his ambitious educational schemes, but it would also pave the way for the mass emigration of black Americans to the island.

While African Americans increasingly eschewed the American Colonization Society (founded in 1816), because the white-controlled organization saw emigration to West Africa as a way to get rid of troublesome free blacks, many still entertained hopes that voluntary emigration to Haiti would provide a sanctuary for African Americans who were facing a rising tide of racism in the northern states.